AI Sovereignty’s Definitional Dilemma

Governments worldwide are racing to control their AI futures, but unclear definitions hinder real policy progress.

Governments around the world are racing to achieve “AI sovereignty.” Fueled by fears of overreliance on a handful of AI technology providers (such as OpenAI, DeepSeek, and Nvidia) and their home countries (notably the United States and China), governments are drawing up new strategies and accelerating investments in domestic AI capabilities to ensure greater agency over their AI technology.

Approaches to sovereignty vary based on different interpretations of the concept. Some countries like Chile and Taiwan are investing heavily in homegrown open-source AI models in pursuit of cultural autonomy, while others, such as France and Brazil, are building institutional capacity for regulatory oversight – also in the name of AI sovereignty. The United Kingdom recently set up a Sovereign AI Unit, whose £500 million in backing is intended to propel AI-driven economic growth and national security domestically. And President Trump’s political posturing at the World Economic Forum in Davos last month further fueled conversations about European AI sovereignty.

But what does it mean to achieve AI sovereignty? Defining AI sovereignty today is like trying to nail jelly to a wall. The concept wobbles between prior, unresolved debates about technological sovereignty from the earliest days of the internet and today’s reality of different actors pursuing often-competing policy goals for AI. As a result, the concept remains systematically underspecified – even as AI sovereignty discussions intensify. We see four reasons why this is the case and urge governments to pursue conceptual clarity by specifying and balancing why and where they want to rebalance their AI dependencies and recognizing the trade-offs.

AI Sovereignty Inherits Unresolved Debates

AI sovereignty is not an entirely new concept. Its underlying aim to pursue greater autonomy and control over technology is an extension of earlier debates over internet, cyber, data, and digital sovereignty. Invoked to justify investments in secure 5G networks, data localization requirements, tighter procurement rules, and other policies, these earlier debates never converged on stable definitions of what is meant by “sovereignty.” This ambiguity has proven politically useful but double-edged: It has offered states the flexibility to rally broad political consensus around wide-ranging policy agendas, but it also provided authoritarian governments with the vocabulary to legitimize censorship, suppression, and surveillance. More often than not, however, it produced much debate with little action, by obscuring important trade-offs and hindering rigorous policy decision-making.

AI sovereignty inherits this vague vocabulary and related unresolved tensions. This makes it difficult to define the concept consistently, measure trade-offs concretely, and operationalize policies without talking past one another. Yet, given the geopolitical importance of AI today, moving toward clarity and specificity in AI sovereignty debates is more urgent than ever.

Different Actors, Different (Incompatible) Meanings

AI sovereignty is invoked to describe very different – and often incompatible – ideas, depending on who is using the term. At the nation-state level, it typically refers to governments wanting more agency over domestic AI capabilities, but even here meanings diverge: “Harder” notions of AI sovereignty emphasize achieving self-sufficiency by ensuring that your country’s AI stack is made up entirely of domestic components; “softer” notions frame sovereignty as strategic autonomy, where governments retain some limited degree of strategic control and regulatory leverage over their AI dependencies. The former is costly and, for the most part, unfeasible for most countries; the latter preserves flexibility but may lead to a false sense of security as AI vendors ultimately retain strategic leverage.

At the same time, private companies and other individual organizations are also increasingly pursuing AI sovereignty. For them, it often means operational control: deploying AI on-premise, avoiding vendor dependencies, and retaining control over data and models. Industry definitions of sovereign AI primarily emphasize technical and organizational control rather than national independence, reflecting the practical constraints organizations face in a cloud- and platform-dominated AI ecosystem.

The fact that sovereignty is used to describe both states’ struggles over geopolitical autonomy and regulatory oversight and companies’ efforts to secure organizational governance further complicates attempts to define AI sovereignty.

Stack-Dependent Interpretations

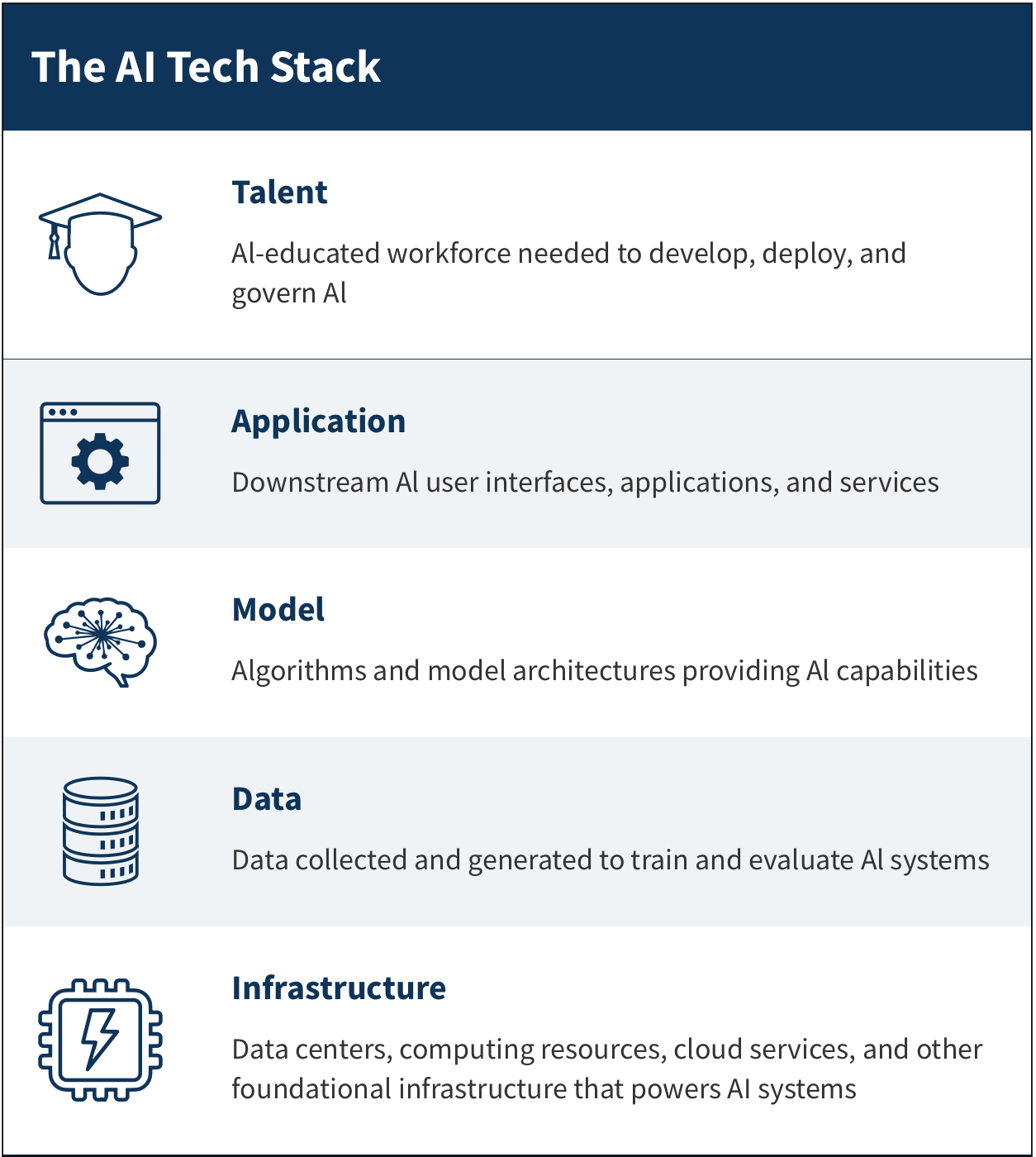

AI sovereignty becomes even more complex once mapped across the different layers of the AI technology stack, meaning the components required to develop, deploy, and scale AI. Each stack layer carries its own competing definitions and degrees of control.

At the infrastructure layer, for instance, sovereignty has been framed as ownership and control over the physical resources that power AI – from electricity and submarine cables to data centers, GPUs, and cloud services. Yet even this dimension is layered: Control over energy differs from control over computing resources, with each existing on a spectrum ranging from pursuing full domestic ownership to securing enough domestic capacity to ensure continuity under crises or softer steering through incentives and procurement. The complexity deepens, as even “compute sovereignty” can be interpreted in multiple ways, from territorial jurisdiction over data centers to the nationality of the firms that own them or the nationality of chip providers. These conceptual difficulties multiply across all the other layers of the stack – data, models, applications, and talent – with differing interpretations of sovereignty leading to contrasting assessments of countries’ sovereignty levels.

At the infrastructure layer, for instance, sovereignty has been framed as ownership and control over the physical resources that power AI – from electricity and submarine cables to data centers, GPUs, and cloud services. Yet even this dimension is layered: Control over energy differs from control over computing resources, with each existing on a spectrum ranging from pursuing full domestic ownership to securing enough domestic capacity to ensure continuity under crises or softer steering through incentives and procurement. The complexity deepens, as even “compute sovereignty” can be interpreted in multiple ways, from territorial jurisdiction over data centers to the nationality of the firms that own them or the nationality of chip providers. These conceptual difficulties multiply across all the other layers of the stack – data, models, applications, and talent – with differing interpretations of sovereignty leading to contrasting assessments of countries’ sovereignty levels.

Goal-Dependent Interpretations

Lastly, countries pursue AI sovereignty for different, and sometimes conflicting, reasons. The goals that are cited most prominently include national security (i.e., making AI supply chains resilient and secure) and economic competitiveness (i.e., ensuring AI deployment creates real, long-lasting economic value at home). But many governments are also driven by an urgent need for regulatory oversight of AI systems, as well as a desire to ensure that AI reflects local cultural, linguistic, and social values and norms.

The result is that AI sovereignty is often a moving target, and that a policy that advances one sovereignty goal may undermine another. Strict data localization, for instance, may strengthen regulatory authority, yet it can also stifle innovation, limit international research collaboration, and introduce national security vulnerabilities. Trade-offs also arise within a single goal: Efforts to boost economic competitiveness by pursuing domestic AI capacity may avoid vendor lock-in and help countries move up the AI value chain, but pushing too far risks lagging behind frontier AI development and slowing economic growth.

The goal of cultural alignment adds yet another complication, as societies differ in what they consider acceptable forms of control and agency over technology. A Māori data governance initiative that emphasizes guardianship and community consent, for instance, illustrates how data sovereignty can be seen as a collective cultural asset – an approach that may contrast with market-driven or state-centric data regimes.

Reorienting AI Sovereignty Narratives

AI sovereignty, then, is best approached by examining the intersection of why a government wants to reduce AI dependencies (i.e., its concrete policy goals) and where it wants to exercise increased agency (i.e., at which layers of the AI technology stack). “Control” alone is not necessarily helpful as an organizing principle: The same locus of control can serve very different objectives, and without specifying those, debates about AI sovereignty risk collapsing into vague calls for ownership.

This is why blanket prescriptions fail. Achieving domestic development across the entire AI stack (the strongest interpretation of sovereignty) is prohibitively costly and unnecessary for most countries. More targeted forms of agency, such as building limited domestic computing capacity for fallback or security purposes, may be justified, but expanding beyond those goals quickly introduces trade-offs in economic efficiency and environmental sustainability.

Sovereignty does not need to be a zero-sum game. Another approach to reducing foreign dependencies is to democratize “control” by joining together with other developers around the world to pursue open-source software for AI development. Having previously played a crucial role in accelerating software development and commercialization, open-source development allows countries to approach the leading edge of AI development while jointly capturing value at home and retaining agency.

The relevant question for policymakers is therefore not “How do we control AI development?” but “How do we strategically manage our AI dependencies – layer by layer – to achieve our national objectives?” The overarching goal should be strategic interdependence.

True AI sovereignty is not about isolation or self-sufficiency for its own sake, but about retaining the capacity to choose – and, if necessary, reconfigure – one’s dependencies based on national strategic priorities, rather than having them imposed.

Researchers at Stanford HAI are currently conducting in-depth research into AI sovereignty, with a white paper to be published later this year.

Juan N. Pava is a research fellow at the Stanford McCoy Family Center for Ethics in Society; Caroline Meinhardt is a policy research manager at Stanford HAI; Elena Cryst is the director of policy and society at Stanford HAI; James A. Landay is a co-director of Stanford HAI, a professor of computer science, and the Anand Rajaraman and Venky Harinarayan Professor in the School of Engineering.