Building a Precise Assistive-Feeding Robot That Can Handle Any Meal

Stanford researchers improve the skewering, scooping, and bite transfer steps.

Eating a meal involves multiple precise movements to bring food from plate to mouth.

We grasp a fork or spoon to skewer or scoop up a variety of differently shaped and textured food items without breaking them apart or pushing them off our plate. We then carry the food toward us without letting it drop, insert it into our mouths at a comfortable angle, bite it, and gently withdraw the utensil with sufficient force to leave the food behind. And we repeat that series of actions until our plates are clear – three times a day.

For people with spinal cord injuries or other types of motor impairments, performing this series of movements without assistance can be nigh on impossible, meaning they must rely on caregivers to feed them. This reduces individuals’ autonomy while also contributing to caregiver burnout, says Jennifer Grannen, graduate student in computer science at Stanford University.

One alternative: robots that can help people with disabilities feed themselves. Although there are already robotic feeding devices on the market, they typically make pre-programmed movements, must be precisely set up for each person and each meal, and bring the food to a position in front of a person’s mouth rather than into it, which can pose problems for people with very limited movement, Grannen says.

A research team in Dorsa Sadigh’s ILIAD lab, including Grannen and fellow computer science students Priya Sundaresan, Suneel Belkhale, Yilin Wu, and Lorenzo Shaikewitz hopes to make robot-assistive feeding more comfortable for everyone involved. The team has now developed several novel robotic algorithms for autonomously and comfortably accomplishing each step of the feeding process for a variety of food types. One algorithm combines computer vision and haptics to evaluate the angle and speed at which to insert a fork into a food item; another uses a second robotic arm to push food onto a spoon; and a third delivers food into a person’s mouth in a way that feels natural and comfortable.

“The hope is that by making progress in this domain, people who rely on caregiver assistance can eventually have a more independent lifestyle,” Sundaresan says.

Visual and Haptic Skewering

Food items come in a range of shapes and sizes. They also vary in their fragility or robustness. Some (such as tofu) break into pieces when skewered too firmly; others that are harder (such as raw carrots) require a firm skewering motion.

To successfully pick up diverse items, the team fitted a robot arm with a camera to provide visual feedback and a force sensor to provide haptic feedback. In the training phase, they offered the robot a variety of fare including foods that look the same but have differing levels of fragility (e.g., raw versus cooked butternut squash) and foods that feel soft to the touch but are unexpectedly firm when skewered (e.g., raw broccoli).

To maximize successful pickups with minimal breakage, the visual system first homes in on a food item and brings the fork in contact with it at an appropriate angle using a method derived from prior research. Next, the fork gently probes the food to determine (using the force sensor) if it is fragile or robust. At the same time, the camera provides visual feedback about how the food responds to the probe. Having made its determination of fragility/robustness using both visual and tactile cues, the robot chooses between – and instantaneously acts on – one of two skewering strategies: a faster more vertical movement for robust items, and a gentler, angled motion for fragile items.

The work is the first to combine vision and haptics to skewer a variety of foods – and to do so in one continuous interaction, Sundaresan says. In experiments, the system outperformed approaches that don’t use haptics, and also successfully retrieved ambiguous foods like raw broccoli and both raw and cooked butternut squash. “The system relies on vision if the haptics are ambiguous, and haptics if the visuals are ambiguous,” Sundaresan says. Nevertheless, some items evaded the robot’s fork. “Thin items like snow peas or salad leaves are super difficult,” she says.

She appreciates the way the robot pokes its food just as people do. “Humans also get both visual and tactile feedback and then use that to inform how to insert a fork,” she says. In that sense, this work marks one step toward designing assistive-feeding robots that can behave in ways that feel familiar and comfortable to use.

Scooping with a Push

Existing approaches to assistive feeding often require changing utensils to deal with different types of food. “You want a system that can acquire a lot of different foods with a single spoon rather than swapping out what tool you’re using,” Grannen says. But some foods, like peas, roll away from a spoon while others, like jello or tofu, break apart.

Grannen and her colleagues realized that people know how to solve this problem: They use a second arm holding a fork or other tool to push their peas onto a spoon. So, the team set up a bimanual robot with a spoon in one hand and a curved pusher in the other. And they trained it to pick up a variety of foods.

As the two utensils move toward each other on either side of a food item, a computer vision system classifies the item as robust or fragile and learns to notice when the item is close to breaking. At that point, the utensils stop moving toward one another and start scooping upward, with the pusher following and rotating toward the spoon to keep the food in place.

This is the first work to use two robotic arms for food acquisition, Grannen says. She’s also interested in exploring other bimanual feeding tasks such as cutting meat, which involves not only planning how to cut a large piece of food but also how to hold it in place while doing a sawing motion. Soup, too, is an interesting challenge, she says. “How do you keep the spoon from spilling, and how do you tilt the bowl to retrieve the last few drops?”

Bite Transfer

Once food is on a fork or spoon, the robot arm needs to deliver it to a person’s mouth in a way that feels natural and comfortable, Belkhale says. Until now, most robots simply brought food to just in front of a person’s mouth, requiring them to lean forward or crane their necks to retrieve the food from the spoon or fork. But that’s a difficult movement for people who are completely immobile from the neck down or for people with other types of mobility challenges, he says.

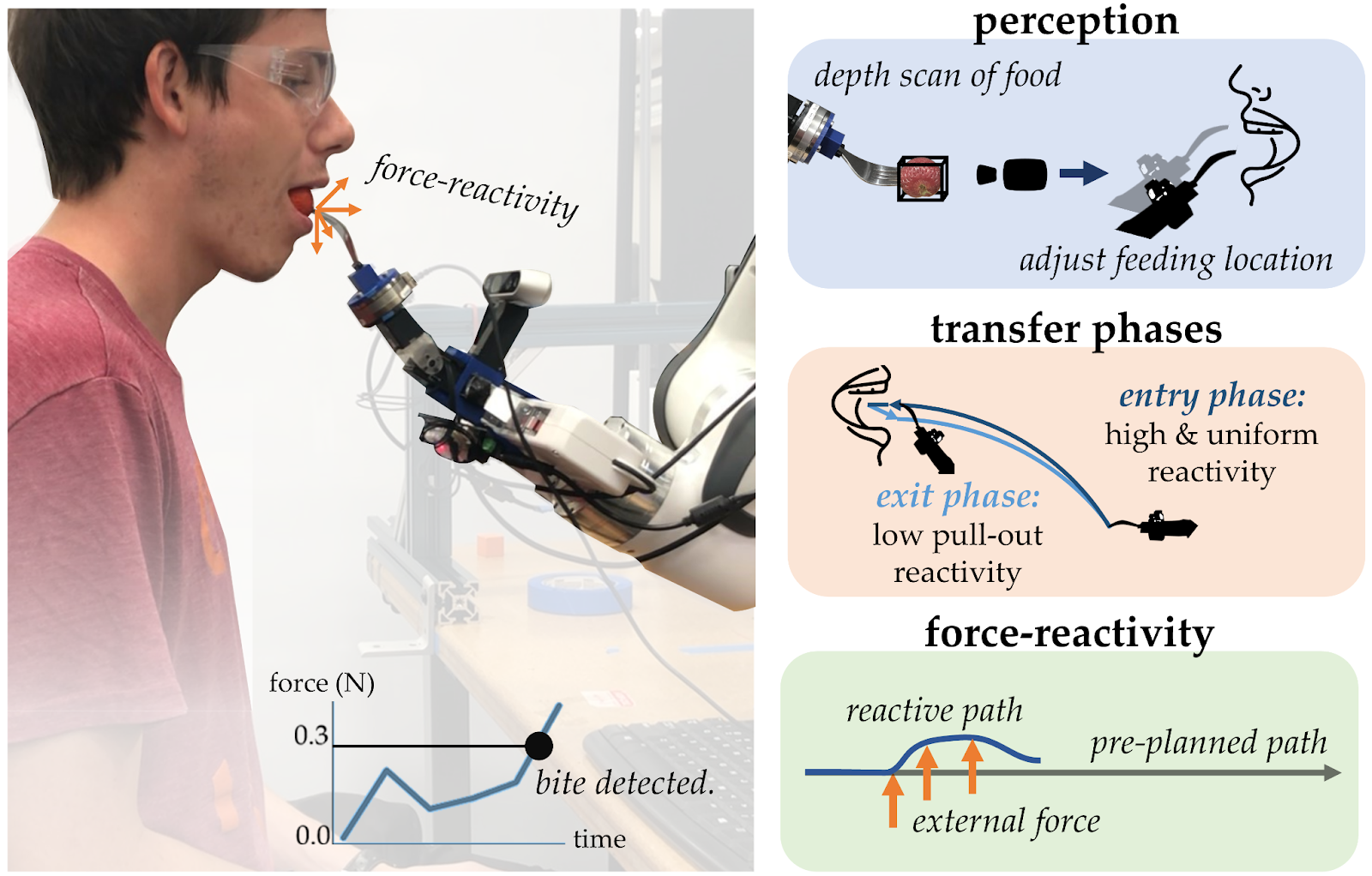

To solve that problem, the Stanford team developed an integrated robotic system that brings food all the way into a person’s mouth, stops just after the food enters the mouth, senses when the person takes a bite, and then removes the utensil.

The system includes a novel piece of hardware that functions like a wrist joint, making the robot’s movements more human-like and comfortable for people, Belkhale says. In addition, it relies on computer vision to detect food on the utensil; to identify key facial features as the food approaches the mouth; and to recognize when the food has gone past the plane of the face and into the mouth.

The system also uses a force sensor that has been designed to make sure the entire process is comfortable for the person being fed. Initially, as the food comes toward the mouth, the force sensor is very reactive to ensure that the robot arm will stop moving when the utensil contacts a person’s lips or tongue. Next, the sensor registers the person taking a bite, which serves as a signal for the robot to begin withdrawing the utensil, at which point the force sensor needs to be less reactive so that the robot arm will exert sufficient force to leave the food in the mouth as the utensil retreats. “This integrated system can switch between different controllers and different levels of reactivity for each step,” Belkhale says.

Algorithms combine haptics and computer vision to evaluate how to insert a fork into a person's mouth naturally and comfortably.

AI-Assistive Feeding

There’s plenty more work to do before an ideal assistive-feeding robot will be deployed in the wild, the researchers say. For example, robots need to do a better job of picking up what Sundaresan calls “adversarial” food groups, such as very fragile or very thin items. There’s also the challenge of cutting large items into bite-sized pieces, or picking up finger foods. Then there’s the question of what’s the best way for people to communicate with the robot about what food they want next. For example, should the users say what they need next, should the robot learn the human’s preferences and intents over time, or should there be some form of shared autonomy?

A bigger question: Will all of the food acquisition and bite transfer steps eventually occur together in one system? “Right now, we’re still at the stage where we work on each of these steps independently,” Belkhale says. “But eventually, the goal would be to start fitting them together.”

Read more:

Stanford HAI’s mission is to advance AI research, education, policy and practice to improve the human condition. Learn more.