"Steampunk" Self-Learning Mechanical Circuits That Adapt to Their Environments

Researchers at Stanford have invented a new type of self-powered mechanical circuits that learn. It could lead to new purely mechanical machines that understand and adapt to the changing world around them.

A team of researchers at Stanford University, led by Manu Prakash, an associate professor of bioengineering who runs a "curiosity-driven" lab, has created the world’s first self-powered mechanical circuits that learn from the environment around them. The advance comes courtesy of the invention of a new mechanical mechanism called Adaptive Directed Springs (ADS).

“The object that we have invented is literally completely new. Strangely, it has no analog in the physical world,” Prakash says. “It’s a meta-material with self-learning ability. One of the reviewers termed it totally steampunk.”

The new spring is, in essence, a mechanical neuron with the ability to change strength over time. Such plasticity is key to the brain’s ability to learn and remember. When connected together in networks, the springs create a material that learns as it is manipulated by external forces.

Thus, a running shoe might adapt the stiffness of its sole as a runner transitions from one terrain to another, sound-proofing materials might actively listen to vibrations and modify themselves to cancel noise, or floating sheets in the ocean might harness energy from passing waves even as conditions change, Prakash says, offering a few potential applications.

The research, partially supported by a Stanford Institute for Human-Centered AI seed grant, is accessible on the preprint server ArXiv.

Hope Springs Eternal

The Adaptive Directed Springs are key to these new mechanical circuits, like the transistors in an electrical circuit yet fundamentally different. Unlike semiconductor transistors that convey information electronically in binary fashion—either on or off, opened or closed, true or false—Adaptive Directed Springs change mechanical stiffness gradually and incrementally based on external forces they experience over time. They have a neuron-like ability to recall a range of stiffnesses rather than the ones and zeroes of binary logic. Most importantly, they are directional in nature and thus can control the flow of information, just as a neuron does in the brain.

“In fact, the precise goal we had in mind when we started was to create this mechanical neuron,” Prakash says of the team’s inspiration. “We wanted to know: Could we create a physical object that could modulate its outputs precisely like a neuron?”

The team consisting of graduate student Ian Ho, postdoctoral scholar Vishal Patil, and Prakash explored many analogies in the living world. One key inspiration came from biology, where Prakash, a bioengineer with deep interest in “embodied computation,” has always been fascinated by the ways simple living cells and brainless marine animals are able understand and interact with the world via mechano-chemical modulations.

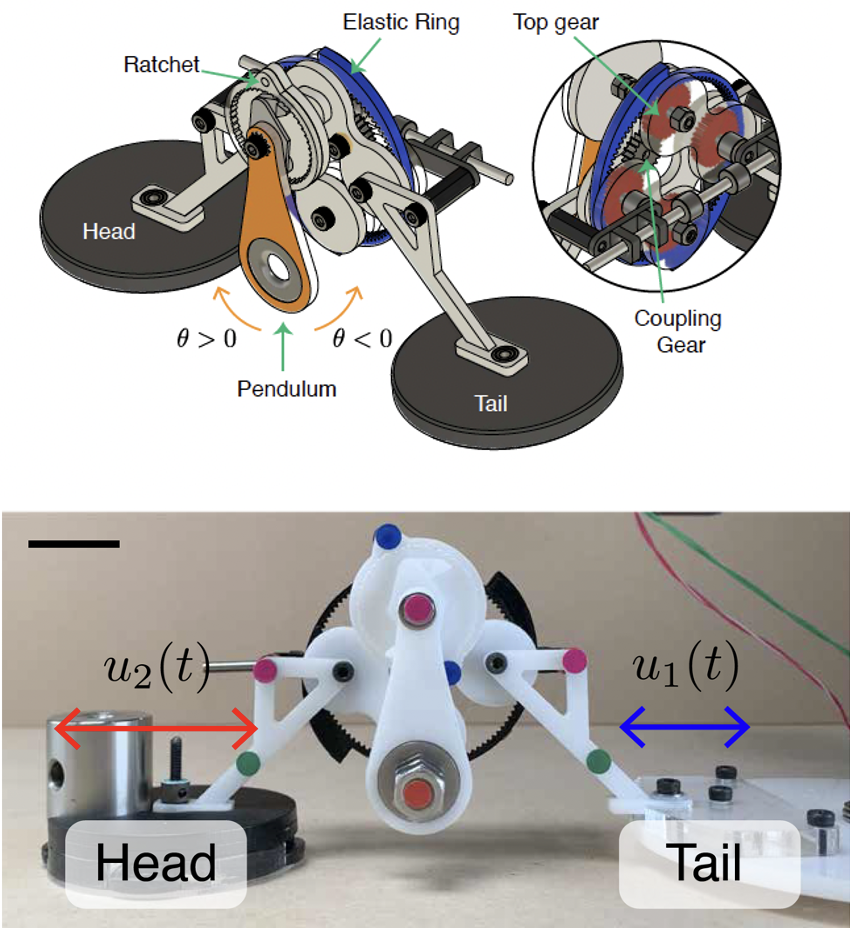

In this Adaptive Directed Spring, the pendulum rocks back and forth, sensing directional force and driving a ratcheted gear that advances the elastic ring. The more it moves, the stiffer the spring becomes. Each time the pendulum pitches forward as the tail rises higher than the head, the ratchet turns the elastic ring another notch, growing stiffer each time. The circuits can continually update themselves in real time.

In this Adaptive Directed Spring, the pendulum rocks back and forth, sensing directional force and driving a ratcheted gear that advances the elastic ring. The more it moves, the stiffer the spring becomes. Each time the pendulum pitches forward as the tail rises higher than the head, the ratchet turns the elastic ring another notch, growing stiffer each time. The circuits can continually update themselves in real time.

Purpose Built

To build their mechanical neuron, the first challenge for the team was to explore how to introduce memory into the system. Ho proposed using closed-loop ribbons with varying stiffness. To self-power the object, the team added an internal pendulum that captures passive energy as the pendulum rocks back and forth. Finally, the team needed to make the spring directional. According to Newton’s Laws of Physics, every action must have an equal and opposite reaction. That is, force is reciprocal and most springs therefore cannot distinguish relative vibrations at their two ends.

“After a lot of trial and error, we finally arrived at what we call a ‘lock-in’ gate, which has gears that move the spring in only one direction, like a rachet wrench,” Ho explains. “That is, it is non-reciprocal.”

All three ideas come together in the novel Adaptive Directed Spring. It looks a bit like a mechanical inchworm with a head and a tail, a pendulum at its belly, all united by a series of mechanical gears. There is an elastic ring (pictured in blue in the diagram) of varying thickness that increases the stiffness as the gears are updated by external forces. That is, the thicker sections of the elastic are stiffer than the thinner areas, providing the key mechanical plasticity the team needed.

The pendulum rocks back and forth, sensing directional force and driving a ratcheted gear that advances the elastic. The more it moves, the stiffer the spring becomes. Each time the pendulum pitches forward as the tail rises higher than the head, the ratchet turns the elastic ring another notch, growing stiffer each time.

This gives the spring its directionality, like the path of electrons through an electrical circuit. It creates an “arrow” of information flow, just as neurons have input and output ends to convey chemical and electrical information in the brain. The spring-based circuits continuously update themselves while in operation—that is, they, in a sense, learn. But, equally important, like biological systems, new patterns can overwrite old ones, a feature that keeps them adaptable and self-learning.

Network Effect

When many of these new springs are united into networks, they create materials that can detect and remember patterns without electronics or software. The circuits are entirely self-powered, requiring no batteries or electrical inputs.

By connecting multiple adaptive directional springs together the team can build mechanical circuits with complex learning behaviors. The topology—how the springs are connected and the directions of their arrows—determines how the network processes information.

Thus, even a simple circuit can have multiple behaviors based on the topology of the connections. For example, a small network might be able to identify repeating patterns in noisy vibrations, remembering and recalling them and reconfiguring when a new pattern appears. Such materials display behaviors that we typically attribute only to the living world. In another configuration, such systems could adapt their stiffness to spread out mechanical strain to act as a mechanical camouflage. In others, they could modulate stiffness necessary for energy harvesting in chaotic environments, like the open ocean.

Future Forward

As such, new materials based on ADS could revolutionize space travel or environmental applications, putting intelligence in materials without the toxic effects of pervasive electronics and batteries. These circuits could function in extreme conditions where electronics fall short—in high radiation environments (the surface of Mars), at extreme temperatures (flag-like generators at the South Pole), or in close contact with living tissue (adaptive bandages).

“With this self-learning context, we can finally start thinking about elastic networks like soft robotics or the trusses of a bridge as circuits that can learn and adapt,” Prakash says. “New network topologies, spring properties, and coupling mechanisms could lead to machines and materials that sense, compute, and act in ways we could never imagine.”